There is an evolving question as to whether PFAS is a dry cleaning problem. A recent Florida study started to answer this question. This article will focus on what PFAS are and summarize some of the Florida study results and what it might say about dry cleaners as a source of PFAS.

If you have not heard of Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA), Perfluorooctyl Sulfonate (PFOS) and other perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) yet, you will soon. For brevity, we will refer to these groups generically as PFAS plural. PFAS are a broad group of chemicals widely used in manufacturing and found widespread in the environment. The 2020 movie Dark Waters starring Mark Ruffalo and Anne Hathaway featured one of the first and highest-profile lawsuits regarding PFAS. PFAS are emerging contaminants that the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) is attempting to regulate. Some states like Michigan, Wisconsin, Florida and New Jersey have gotten out in front of the USEPA and have established state regulatory limits for a small number of the more commonly used compounds.

First, the “what”: PFAS are part of a broad chemical group first developed in the 1940s. Since then, manufacturers have introduced over 4,000 PFAS compounds into the production of consumer goods both as primary and secondary components. Some of these compounds are being phased out due to toxicity concerns; however, manufacturers are developing new fluorinated compounds like Gen X and ADONA to replace them. Many PFAS are banned from use and import in manufactured goods in the United States.

Well known for their unique chemical properties, PFAS repel oil and water and resist temperature, chemicals and fire. These are the attributes that make PFAS attractive and are why so many durable industrial and everyday products like non-stick surfaces, fire fighting foam as a flame retardant, stain resistant fabrics, water repellent coatings and plating demisters contain PFAS.

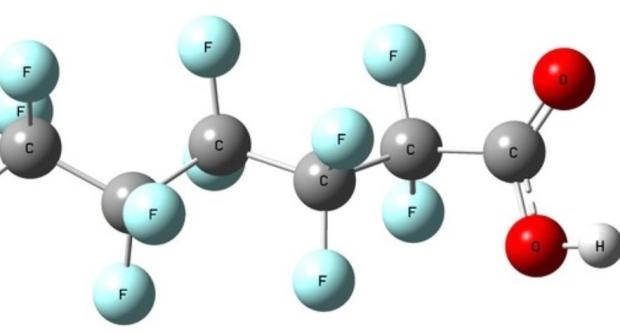

The chemistry is complex because PFAS are not one chemical compound; they are a class of chemical compounds that share the common carbon-fluorine bond. The carbon to fluorine bond is one of the strongest bonds in organic chemistry, making PFAS compounds particularly resistant to degradation and therefore cleanup. Since they do not break down and they have widespread use, they are being found everywhere in the environment.

Sources of PFAS

The USEPA first announced PFAS health advisories in the May 25, 2016 Federal Register. Since then, numerous updates and significant research has been published by USEPA, State Agencies and private researchers. After which, State regulatory agencies began pushing primary and secondary industries into investigate for PFAS. To date, most of the investigation and cleanups have centered on both the manufacturers of PFAS compounds and military airports. The three general sources of PFAS impact on the environment include:

• Primary: Manufactures of PFAS Compounds

• Secondary: Manufactures of Items with PFAS or direct use of PFAS compounds

• Tertiary: Use/Disposal of PFAS containing products

The manufacturers of the PFAS compounds generally include the large chemical manufacturers that have been the subject of much regulatory scrutiny and private litigation. The secondary group includes all the industrial and commercial processes that directly applied these chemicals to products or processed materials previously coated. Dry cleaners that offered the application of stain-resistant coatings containing PFAS fall within this second group but also fall within the third group.

The third group is comprised of all consumer and commercial use and disposal of PFAS treated products. The potential for PFAS impacts to the environment from this third group is probably least understood. This third group is where dry cleaning may have its most significant exposure for PFAS impacts since dry cleaning by-products (spent solvent, lint, still bottoms, etc.) have had contact with PFAS containing textiles.

We know historically dry cleaners accidentally released solvents to the environment, but how much PFAS were in these spent solvents? Studies from Toronto University have shown fast fashion items contain high levels of PFAS and other contaminants at levels that cannot be coincidental. When these PFAS laden clothes are washed, PFAS can accumulate in the various waste streams and mechanical vents at dry cleaners. Additional studies show that cosmetics also contain high levels of PFAS. Clothing with cosmetics stains may also contribute to low level accumulation of PFAS in facilities that would concentrate wastes. That is to say, dry cleaners, through filtration processes, concentrate PFAS, which may then enter the environment incidentally near waste storage and vent discharge points at dry cleaning and laundry facilities.

Testing of Drycleaning Samples

The Florida PFAS study evaluated both virgin and spent dry cleaning products from seven (7) Florida dry cleaning facilities. Virgin cleaning products at two of the seven facilities contained detectable concentrations of PFAS. One facility had a small detection of PFAS in a dry cleaning machine cleaner and the other facility had a more substantial detection in a virgin petroleum-based solvent mixed with soap. Some virgin dry cleaning products do contain PFAS. The take-away message for you is to ask your chemical supplier for details on what is in your incoming products.

PFAS were detected in dry cleaning wastes (spent solvents, solids, filters) in six out of seven of the facilities tested. PFAS compounds on treated fabrics clearly come off the fabrics during the cleaning process and are concentrated in the resultant waste products. Although use of some of these compounds have been phased out years ago, you can probably expect to see this continue for a while.

The Florida study went even further and evaluated PFAS in virgin and spent products from seven wet laundry facilities. One out of four laundry detergents contained PFAS at relatively low levels. However, PFAS were detected in every wastewater discharge sample analyzed. PFAS clearly come from treated clothing even during a wet laundry process, although to a lesser extent than from dry cleaning. One interesting finding of the study that speaks to the ubiquitous nature of PFAS is that they were detected at low concentrations in the incoming potable water at most of these facilities.

Testing of Soil and Groundwater

In the Florida study, ten sites with known dry cleaning solvent contamination (chlorinated and petroleum based) were evaluated. Eight of these sites had undergone some level of remediation. Samples of soil and groundwater were collected and submitted for analytical testing for 28 PFAS and GenX compounds. PFAS compounds were detected in groundwater at all ten sites. While the presence of PFAS seemed to correlate to the presence of PCE there was little correlation between concentrations of PFAS and PCE. This is likely due to how these compounds behave in the environment.

The study did identify four sites where it appears there was PFAS entering the site from an off-site source. Again, given PFAS widespread use and their propensity to not degrade, this is not entirely unexpected. However, even at these four sites, there was evidence of PFAS contribution due to the releases of dry cleaning products.

Similar results were seen in soil samples collected and submitted for laboratory analysis. Although all the soil sample detections were below levels deemed safe by Florida for direct exposure, they were above levels that have the potential to impact groundwater above safe levels.

Dry cleaners inadvertently introduce PFAS compounds through the chemicals they use. Going forward it’s important that dry cleaners document the PFAS content of incoming chemicals from your suppliers and if possible avoid PFAS containing products. What is clear is that the dry cleaning process itself introduces PFAS into your waste streams by extracting them off of the stain resistant garments. How big of a problem this will be for the dry cleaning industry is unknown as the science and regulatory framework surrounding PFAS is evolving.

Responding to Regulatory Requests

Should someone ask you to sample for PFAS compounds at your site, what should your response be? First and foremost, your response should be a cautious one made with input from a qualified consultant and potentially legal counsel. It should be clear under what authority the demand is being made and what some of the ramifications might be should PFAS be found on your property. If the decision is made to proceed, you will want to consider:

1) What PFAS compounds am I being asked to sample for?

2) What analytical methods will be acceptable to the entity asking for these results?

3) To what criteria will the results be compared to?

4) Are there other sources of PFAS surrounding my property?

5) Will my consultant control the accidental introduction of PFAS into environmental samples?

6) What are the consequences of not responding?

7) Is any of this data confidential?

The Consequences of a Release

Currently it is difficult to say what will be required should you discover a release. One thing that is certain is that the cleanup of a PFAS release, to likely very low cleanup standards, will not be easy. The amount of research into PFAS cleanup being conducted at this time by commercial and private companies is staggering. Promising interim technologies are being developed by the not-for-profit Batelle research organization and others. It is likely that the best solution will present itself in a technology yet unknown to us at this time.

Because of PFAS chemical structure, they are recalcitrant and do not lend themselves to many of the chemical and biological processes traditionally employed to remediate dry cleaning solvent plumes. Research is being conducted but as of now there are few in place options for soil and groundwater remediation. The physical removal of the compounds from soil and groundwater is, for now, likely the best remediation option. Excavation of soil and the pumping and treating of groundwater are two ways of physically removing PFAS from the environment. Physical removal of these compounds creates waste products that need ultimate disposal. Heat destruction of these waste products offers promising results; however, the temperatures required are difficult to achieve and economically unsustainable

Conclusions

The Florida study indicates that PFAS may well be an issue at drycleaner cleanup sites. Prior to implementing any sampling efforts that may put you in the liability hot seat, make sure you are thoroughly engaged with a consultant and legal counsel that can outline your options.

The USEPA will within the next two years establish certain PFAS as a hazardous substance, which will make it easier for them to regulate. Without the hazardous substance designation from the EPA, investigations and remediation vary by State. PFAS sampling is more expensive than traditional environmental sampling and because the remedial options are limited and the regulatory framework is still up in the air, your long-term costs and liabilities are difficult to predict.

Authors – Brad Lewis, CHMM, Principal Scientist and Rob Hoverman, LPG, Northern Midwest Regional Director

Resources

Detailed information on the State of Florida efforts regarding its studies including the white paper can be found on the Florida Department of Environmental Protection web page: https://floridadep.gov/waste/waste-cleanup/content/drycleaning-solvent-cleanup-program-state-funded-pfas-sampling-efforts

The US EPA offers resources and references to various State programs on its PFAS page: https://www.epa.gov/pfas

1 Florida Statewide PFAS Pilot Study at Drycleaning Sites, Florida Department of Environmental Protection, Nicholas Barnes, P.E., Fabio Fortes, P.E., Ziqi He, PhD, P.E. and Steven Folsom, P.E., BCEE,

By: Brad Lewis and Rob Hoverman – EnviroForensics